Star serialisation - Trashcan Child

Ah, here finally comes the first part of one of Dark City's Star serialisations. I had a hard time choosing 'sanitary' stories for newspaper publishing, I can tell you:)

http://thestar.com.my/lifestyle/story.asp?file=/2006/11/26/lifebookshelf/16124577&sec=lifebookshelf

Trashcan Child

When a woman who doesn’t want to be a mother is given a baby nobody wants, things can take a macabre turn. This is the first of a two-part condensation of Trashcan Child, one of the stories in Dark City: Psychotic and Other Twisted Malaysian Tales, by Xeus.

AS the most splendid sunrise ignited the universe, lighting treetops and their slumbering winged tenants into an explosion of birdsong and morning, the baby awoke.

The first thing she did was to stretch herself, bunching up her fists to strike at surrounding objects; her little hand encountered a soggy wetness, a mushiness alien to anything she’d ever felt before, and she withdrew it sharply.

With the smells came a more familiar sensation, the belaboured effort to breathe, to fill her lungs with deep, pungent air and her starved brain with oxygenated clarity. Her little chest rose up and down rapidly as it worked itself up, sparking little black and gold stars in her vision as a wave of dizziness swept across her. Yesterday was a struggle too, when she had been half-submerged in that sticky fluid; she had inhaled it, and the insides of her windpipes had been seared with a sudden agony. Through her watery prison, a woman’s shadowed face rippled, with hooded eyes, quivering mouth in a semblance of weeping. The baby had smiled up at that face, held up her arms to be embraced (but couldn’t, because they were pinioned), and so she opened her mouth ‘O’ style to eke out a like-shaped bubble, which rose lazily to dissipate at the surface.

The baby waited, and she wasn’t disappointed. Along came the crunch of footsteps on gravel. A shadow fell across the edge of her bed, and a face peered down, framed by blue sky. Pretty smiling eyes accompanied by dimpled cheeks.

“Oh, my goodness me. You poor baby. Who could’ve put you in a trashcan?”

The words were unintelligible to the baby, but she smiled anyway, sensing rescue and possibly a whole new world than that which she had been born into. . And indeed, firm hands clasped her shaking body and lifted her up, holding her close. Warm, warm flesh and the soft smell of flowers.

******************

From her paned windows upstairs, Ida could see the woman approaching, bundle in her arms.

But I don’t want this.

It’ll be good for you. To have someone to care for other than yourself.

Can’t you find someone else? Someone more ... appropriate? Someone who actually likes children?

Ida. We’ve talked about this.

The doorbell rang, a booming chime in the blessed stillness of the house. I still don’t want this, Ida thought as she made her dignified way downstairs, past a child’s bedroom with a freshly painted cot (her old baby cot, kept by her late mother in the hope that she would have a baby of her own some day). Carefully chosen landscape paintings hugged the walls of the hallway and landing, alongside carefully displayed vases, crystal and a potpourri of fragile collectibles.

Of particular reverence, at least in terms of holding centre court, was a beautiful Ming Dynasty urn in the living room display cabinet. This was surrounded by lush Italian furniture, embroidered in red and gold thread, upon which were now draped objects unfamiliar to the house: a new child’s blanket, several diaper bags and a hamper of baby clothes.

Through the frosted glass panels of her oak door, Ida could see the geometrically distorted head of Pearl. She opened it.

On the terraced steps leading up to the door, alarmed by the sudden intrusion, the baby in Pearl’s arms began to cry. Ida’s mouth immediately flattened into a firm, thin line.

“Oh, come now, Ida, don’t look like that. You were a baby once. I’ll bet you cried too,” Pearl admonished.

“I’ve never liked babies. I told you that. Never liked children or teenagers either. Can’t abide the noise and the fuss. Always crying. Always demanding something.”

“Not all children are like that. It’s how you bring them up.”

Pearl handed her the baby. “Here. Hold her like this. That’s right. Support her neck like this. She can’t hold up her head yet.”

Ida clasped the crying baby to her chest, grimacing as she tried to get a comfortable fit. How did one hold a crying baby?

Were you supposed to coo or ignore them till the noise went away? The baby felt alien in her arms, like a guilty burden that weighed too heavy for its own good.

“How do I get it to shush?”

“Now, Ida, it’s a ‘she’, not an ‘it’. Talk to her a little. Hold her close to your bosom. She’ll calm down after she gets used to you.”

The baby wailed louder. Ida held it away from her body in distaste. “Here. You take her back. You’re better with babies.”

“No, I won’t.” Pearl back-stepped lightly. “You’re going to have to get used to this all by yourself.”

“But I don’t know anything about babies!”

“You have the books. You have everything you need. Like any other new mother, you’re just going to have to experience it for yourself.”

“I’ve never wanted to be a mother,” mumbled Ida beneath her breath. “I’m too old.”

“I’ll come back on August thirteenth, at half past seven am.”

August thirteenth! Almost a whole year away. “But I can’t look after her all this while. She’ll need a proper home.”

But Pearl had already turned tail. She was walking abruptly down the drive.

“Wait! What shall I call it ... I mean her? What’s her name?”

“She doesn’t have a name! You’ll have to find her one. And remember, I won’t be in contact till August thirteenth!”

“But what if I need to call you or ask you something about the baby? How will I get in touch?”

“You won’t need to.”

And with that, Pearl disappeared, leaving Ida all alone with the baby.

******************

The sound of crying once again wafted from the baby’s room at the other end of the corridor. Every night for the past two weeks, the infant had woken up at two-hourly intervals, as though she was a clockwork doll designed to torment.

Why couldn’t the cursed child stay asleep? Surely she couldn’t be hungry again?

As she wearily got up, Ida reflected on the reasons why she had remained childless. The Australians had a term for this: she was not “clucky”. She had no desire to be a mother hen, and if she had a biological clock, it was in need of greasing. But it was precisely this: the nighttime terrors, the profound weariness which she suspects will worsen as the months take their toll, and the sense the rewards would not commensurate with the effort put in. She had always seen babies as a chore, an extra mouth to feed (and at ungodly hours), a little wriggling bundle to zap her away from her precious interests: like collecting antiques, reading and sipping tea on the terrace, going to the spa and having a facial.

Indeed, for the past two weeks, she had neither the time nor the energy to do the things she liked. The book she was reading, Paulo Coelho’s latest, remained dog-eared at the very spot she’d left it when she had been waiting for Pearl and the child.

In the cot, the baby’s face was puckered a furious red. As Ida forced the bottle into her open mouth, she began to suck lustily. It was still “she”, Ida had not progressed to naming her yet. She finished the entire two ounces, spat out the teat and burped on her own accord. Then she promptly fell asleep on Ida’s shoulder, drool spooling down her guardian’s silk pyjamas.

Drat. If I put her down on the cot, she might wake up and start crying again. Ida couldn’t bear the sound of crying; it grated on her nerves, like squeals on a chalkboard. And yet, she retained a sense of responsibility to the child. It came from long-standing penitence; she would never be an intemperate caregiver, like so many guardians are wont to be.

Brain numbed from accumulated fatigue and half-conscious of what she was doing, Ida shuffled back to her own bedroom, baby still slung like a sack of potatoes across her shoulder. She crept into her rumpled bed and lay down flat, the baby still tucked into the angle of her back and shoulder. Before she knew it, she had awoken. The sun was streaming through the windows and it was high morning.

The baby had slept for a good six hours.

The next night, Ida dragged the cot into her bedroom. But the baby never slept as well as when she was next to Ida in bed. Just the nearness of Ida alone seemed to calm the child down, so that she slept through the night.

At the end of the month, Ida named the baby Patience, for their shared experience of that certain virtue.

******************

The year passed uneventfully. Patience learnt to crawl, walk and say “Mama”. Ida marvelled at each milestone even as the baby doubled in weight and size.

“Don’t call me Mama. I’m not your Mama. And this is only temporary, lest you get too comfortable.”

“Mama,” insisted Patience.

“On your Special Day, you’ll have a new Mama.”

August thirteenth became the Special Day, the eagerly awaited hour when Ida would gain her redemption and Patience would be carted away to a better home. Ida was not sorry Patience was leaving. It was time for a new beginning. There had been satisfying moments, like when Patience took her first step and said her first word. But Ida was not mother material; she retained no firm attachments to the child other than a vague fondness, like that of a nanny or governess. She felt no kinship. Perhaps what the old wives said was true: one could not love a child unless the same blood flowed in their veins.

But still, there were moments of bliss. Like the pure unadulterated look of joy on Patience’s face each morning when she cried “Mama”. Of being the centre of the child’s (someone’s) universe.

On August thirteenth, the two of them woke up early. Ida dressed Patience in her best baby frock, the one with the pretty blue bows, and topped it off with the cutest white bonnet.

“Someone will be coming for you. You’ll have a new home, and new clothes.”

“Mama,” Patience said, holding out her arms to Ida.

Maybe I’ll kind of miss the little tot, Ida mused. But it was time to move on. Thinking of tomorrow, she was almost filled with dread. But there’s nothing to worry about. You’ve earned it.

Half past seven came and went like a bee cruising through their home. As Ida and Patience waited, the sun rose high, evaporated the dew and wilted the flowers, and still no one came. At midday, they ate sandwiches and mashed peas on the terrace. At twilight, as the shadows grew long and the sky turned to dusk, Ida took off Patience’s bonnet.

“Home,” Patience said.

“That’s right, we’re going inside.” Time for bed. “Maybe they’ll come for you tomorrow.”

“Mama,” Patience retorted, and grabbed fistfuls of Ida’s hair as she was carried inside the house.

Part Two of ‘Trashcan Child’ next week.

5 comments:

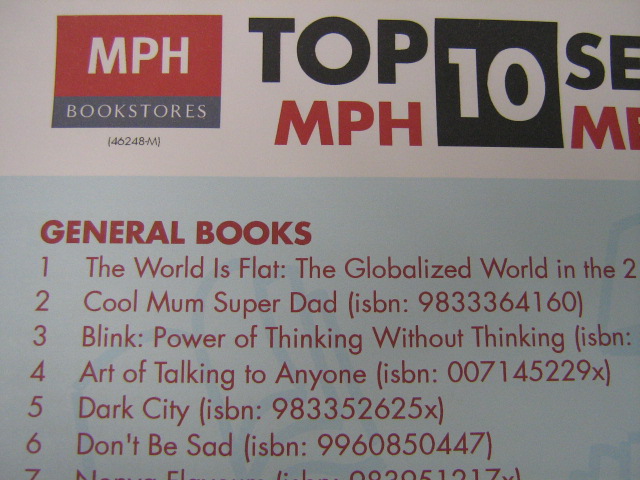

When is the closing date for Dark City 2 submissions? Thanks!

Feb 28th 2007. Details in the Sidebar of this blog.

Yohooooo....was surprised and delighted to see the extract from your book. What a clever idea to publicise local authors!

That was really a tasty bit ( as Sharon Bakar puts it, I think) and let's hope more people will get their hands on Dark City instead of waiting for the next installment!

You go, girl! Did June pick 'Trashcan Child'?

Yvonne, it's June Wong's idea actually.

Argus, I chose 2 sanitary stories for them and Malini chose this one.

Post a Comment